This blog post is about some features of C# language. Sometimes, as I am thinking about a certain language feature, I ask myself why something is the way it is. Some questions find immediate answers. Mind you, the questions are almost always rather obscure and perplexing. For example, it is immediately clear why interfaces cannot contain other interfaces. It’s because a nested interface implementation is not different from a non-nested one. However, for other questions I don’t have immediate answers and have to spend some time thinking. Take a look and see how many of them you can answer easily. I am providing my answers right below.

- Why is it only possible to have one static constructor in a class?

- Why is it not possible to declare a class or a struct inside a method?

- Classes can be nested. Can methods contain methods? Can methods contain delegates?

- Why static constructors can only operate on static fields?

- Do structs receive default parameterless constructors if no constructor is provided in the struct definition?

- It is possible to have checked{} and unchecked{} regions of code. What is the default behavior?

- Why is it not possible to specify an access specifier on a static constructor? What is the provided access on static constructors?

- Instance constructors are not inherited. Are static constructors inherited?

- Will a class that has only a static constructor receive a default instance constructor?

- What is the output of the following piece of code:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

namespace TestingStatic

{

class Test

{

public Test()

{

t = 3;

Console.WriteLine("Inside instance constructor");

}

static Test()

{

t = 4;

Console.WriteLine("Inside static constructor");

}

public static int t;

}

class EntryPoint

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Test thisTest = new Test();

Console.WriteLine(Test.t);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

}

Why is it only possible to have one static constructor in a class?

A static constructor is invoked when a class is used for the first time. If there were two or more static constructors, then the runtime would somehow need to know which one it should call. A static constructor cannot have input or output parameters, thus purely syntactically two static constructors in a class definition would have identical signatures. This makes it impossible to define more than one static constructor, but makes it very clear for the runtime which one should be invoked.

Why is it not possible to declare a class or a struct inside a method?

This questions can be answered in several ways. My favorite answer stems from the language design and type hierarchy. If you have a better answer – please let me know.

So, C# constructs can be broken into types and members. The types are: classes, structs, interfaces, delegates and enums. The members are fields, methods, indexers, properties, events, operators, constructors and destructors. Are you thinking that an int is also a type? Yes, it is, but it is a primitive type which, under the above hierarchy, is simply a field. The main design idea is that types contain members that perform some operations. Here ‘contains’ means defines and operates on.

A certain inner hierarchy exists within the types. At the top we have classes and structs that can contain all members and some other types including other classes and structs. It would not make sense for a class to contain interfaces, because this would mean they still need to implement them as well. So, we could say a class ‘contains’ an interface when it implements it. Interfaces follow classes in the sub-hierarchy. Interfaces can contain some members only, like methods, properties, events and indexers. Then come enums that can only contain named constants. Delegates are the last in this sub-hierarchy: they cannot contain any types or members, but they are still types.

Members cannot contain types. Members cannot contain other members, except for fields. For example, a method can declare its own local fields of primitive type, like int, object or string. Constructors, destructors and events are forms of methods. Properties are extensions of fields, and they are also methods. Methods cannot contain other methods. Events are fields, but of delegate type.

Classes can be nested. Can methods be nested? Can methods contain delegates?

Just like the answer to the second question above, no, methods cannot contain other methods. Methods cannot define delegates, because members cannot contain/define named types.

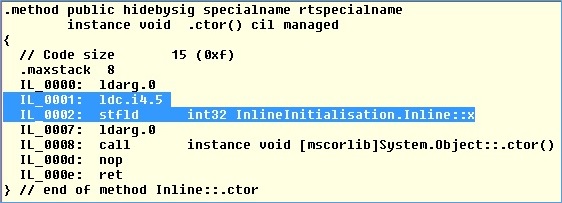

Why static constructors can operate only on static fields?

This has to do with the order in which static and instance fields and constructors are allocated in the memory and initialised. When a class contains static fields and/or static constructor, the order of field initialisation is the following. The static field initializers execute before the static constructor. Thus, when these fields are referenced in the body of a static constructor, which happens next, they are already initialised. At the point of static constructor invocation, no instance fields have been yet initialised by the CLR. This happens next, and it is followed by the instance constructors. So, static constructors can only operate on static fields, because non-static fields are not guaranteed to have been properly type initialised by the CLR at the point of execution.

Do structs receive default parameterless constructors if no constructor is provided in the struct definition?

The answer is yes, because all value types receive an implicit parameterless constructor. This makes it possible to declare structs and other value types using new keyword. Also, because a parameterless constructor is provided, no parameterless constructor can be defined/overloaded in the struct (Note: true for C# up to C# 6.0!). However, structs can define own constructors with parameters. Note that, unlike with classes, this implicit parameterless constructor is not visible in ILDASM.

It is possible to have checked{} and unchecked{} regions of code. What is the default behavior?

The default, if one can call it default, is unchecked. However, this is only if the compiler is invoked without the ‘\checked’ or ‘\unchecked’ options. Some people become surprised when they realise that overflow occurs silently in the unchecked region of code. However, before you decide to use ‘checked’ from now on, consider the impact on performance.

Why is it not possible to specify an access modifier on a static constructor? What is the provided access on static constructors?

Static constructors are always private. It is not possible to override this access modifier, thus it is not possible to specify an access modifier on a static constructor.

Instance constructors are not inherited. Are static constructors inherited?

No they are not inherited. No constructors or destructors are inherited.

Will a class that has only a static constructor receive a default instance constructor?

The answer is yes, it will receive a default parameterless constructor. This is because it still should be possible to create instances of such class with the new keyword. Note that this is true for non-static classes only. Static classes do not receive a default parameterless constructor.

What is the output of this code?

The output is given below. You should be able to understand why this is the output if you understand the answer to question 4:

Inside static constructor

Inside instance constructor

3

I hope at least some of you found this useful. Let me know if you think any of my answers can be improved upon!